Download PDF

[Seeing how quickly a collection of HTML-based maps will load within our CMS]

Testing out a map with a title:

Map with shorter title:

Complete archive of all research reports and briefs

Download PDF

[Seeing how quickly a collection of HTML-based maps will load within our CMS]

Testing out a map with a title:

Map with shorter title:

October 2025 | by David C. Dollahite, Loren Marks

October 2025

by David C. Dollahite, Loren Marks

A new report from the Institute for Family Studies explores the link between the Success Sequence and mental health among young adults when they reach their mid-30s.

Download PDFAmerica is facing a mental health crisis. Suicide, anxiety, depression, and drug overdose deaths have all risen to record levels. Younger generations have been hit especially hard during this crisis. Millennial men and women experience increased anxiety and depression compared to previous generations at the same age.

Some argue that the emotional state of young adults today is related to their financial precarity. Economic pressures such as student loans add stress in young adults’ lives, and Millennials have also encountered many obstacles in the workforce, including a challenging job market and longer work hours.

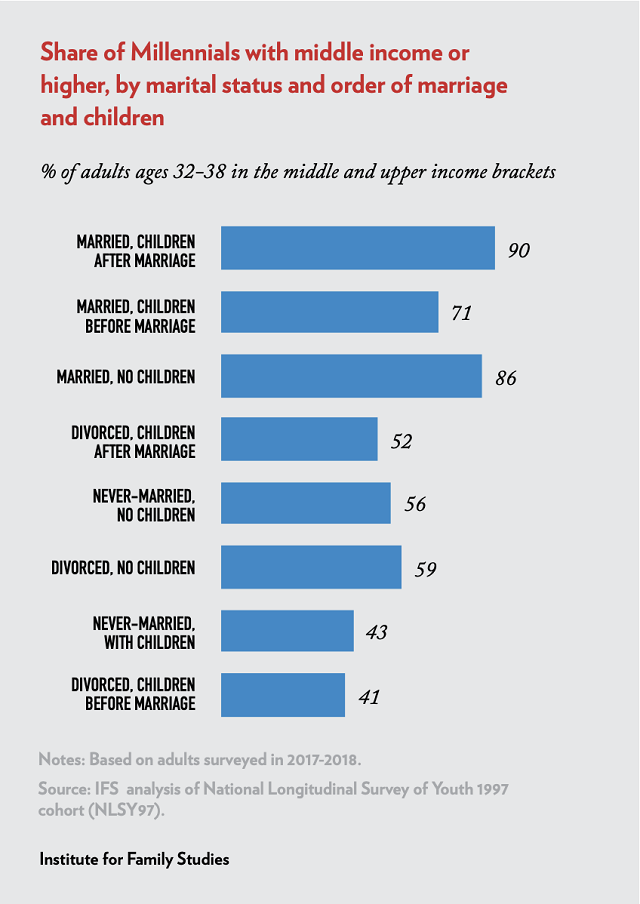

Meanwhile, there is a path that young adults who aspire to move up the economic ladder and establish a financially secure foundation should follow: Get at least a high school education, work full-time, and marry before having children. Among Millennials who followed what is known as the Success Sequence, 97% are not poor when they reach adulthood, and 90% reach the middle class or higher. Young adults who manage to follow this sequence—even in the face of various disadvantages—are much more likely to flourish financially.

In addition to offering robust financial benefits, could the Success Sequence also help young adults flourish emotionally and achieve better mental health outcomes? Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), a new report from the Institute for Family Studies explores the link between the Success Sequence and mental health among young adults when they reach their mid-30s.

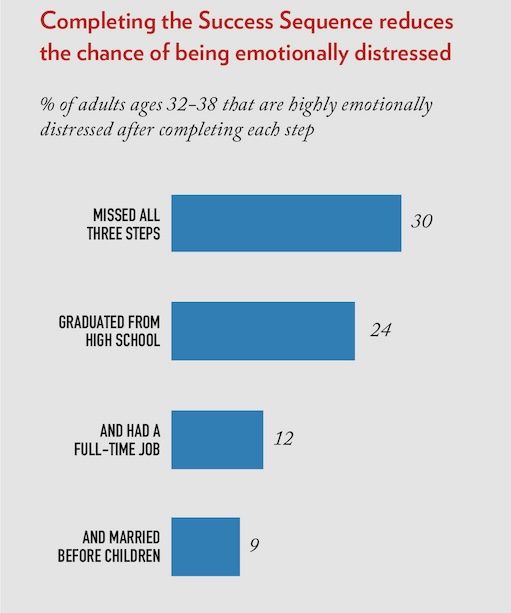

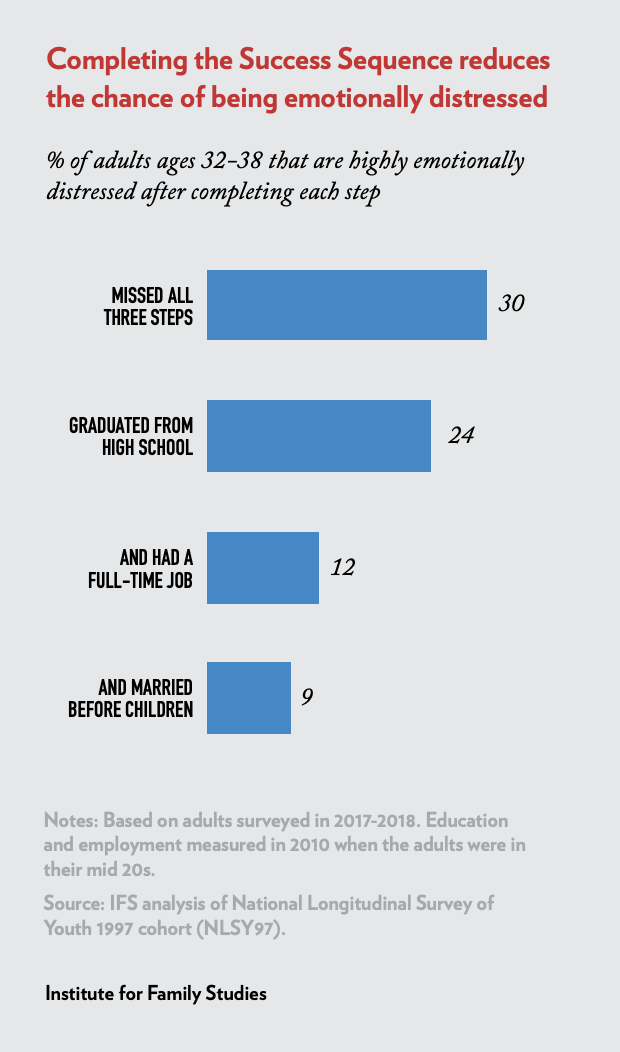

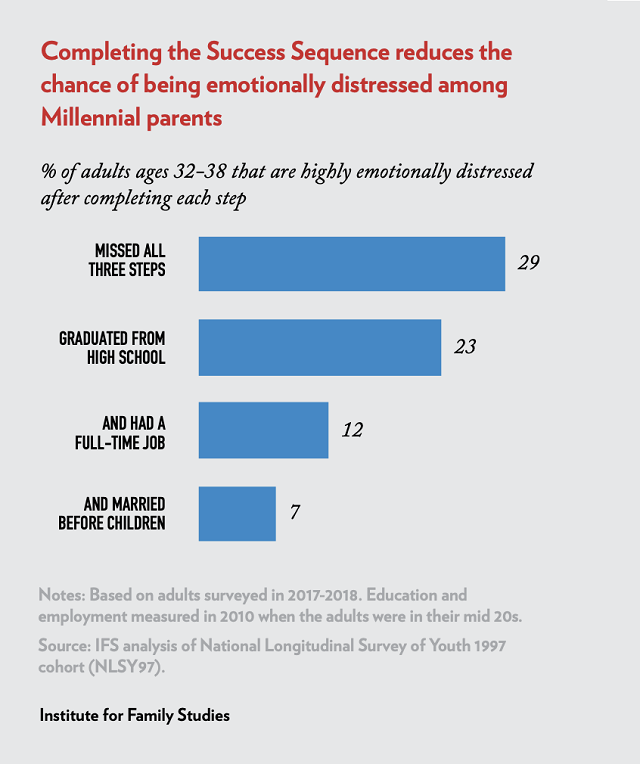

We find that the Success Sequence is strongly linked to better mental health among young adults. Our analysis of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) in the NLSY97 demonstrates that the incidence of high mental distress at ages 32 to 38 drops dramatically with each completed step of the sequence. Millennials who completed all three steps are much less likely to be highly emotionally distressed by their mid-30s, compared with those who missed these steps (9% vs. 30%).

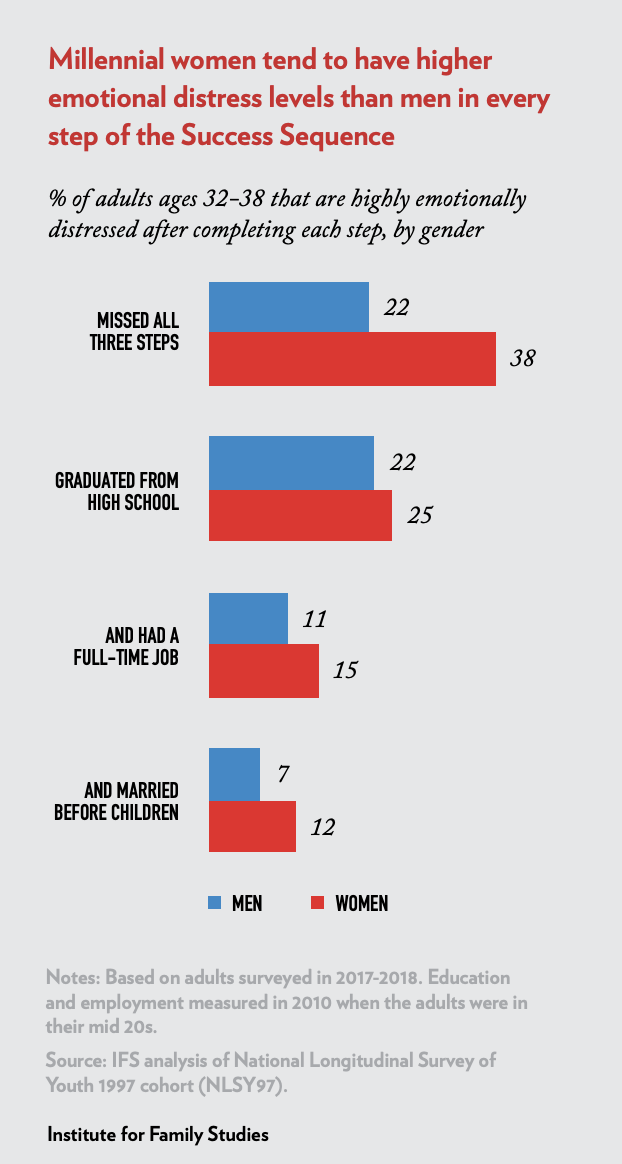

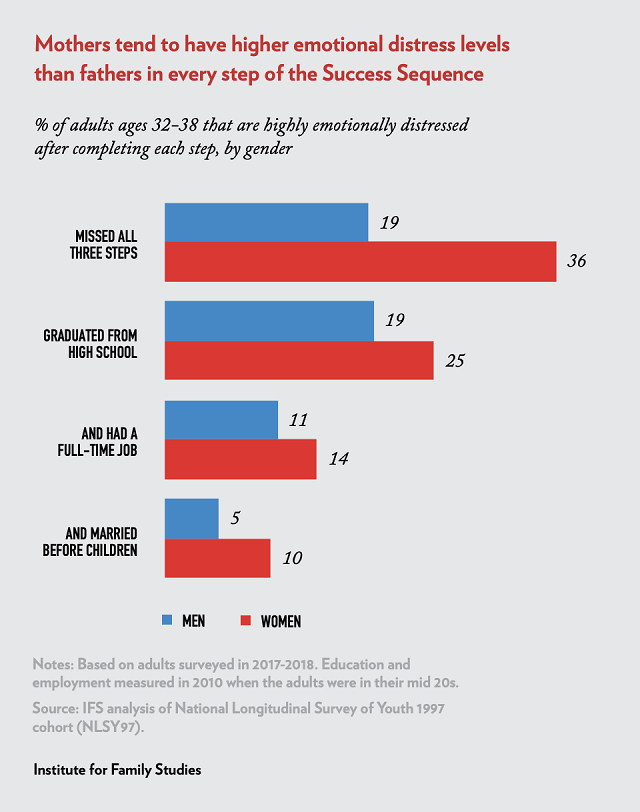

At the same time, there is a gender gap in mental distress among Millennials. Women are consistently more likely than men to report experiencing emotional distress. The gender gap is the largest among Millennials who missed all three steps of the Success Sequence (38% vs. 22%). But even among those who followed all three steps, women are still more likely than men to experience higher emotional distress (12% vs. 7%).

A racial gap also exists in mental distress among Millennials. White young adults who missed all three steps of the sequence by their mid-30s seem especially more likely to suffer from mental distress than other racial groups. Among this group, 38% of white young adults reported being highly emotionally distressed, compared with 23% of black and 26% of Hispanic young adults. This racial gap narrows with the completion of each step of the Success Sequence and is almost closed among young adults who have completed all three steps.

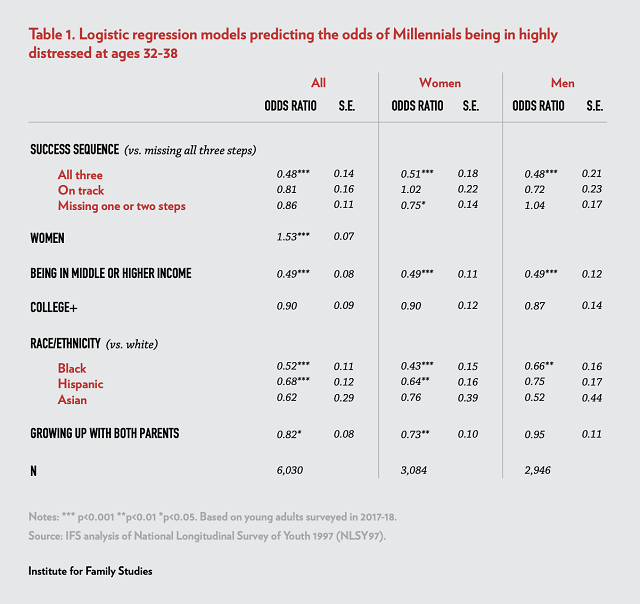

It is tempting to link better mental health to the financial success of the young adults who completed the Success Sequence, but the findings suggest that even after controlling for income, the sequence remains a significant factor in predicting your adult mental health. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress by their mid-30s are reduced by about 50% for young adults who have completed the three steps of the Success Sequence, after controlling for their income and a range of background factors, including gender, race, and family background.

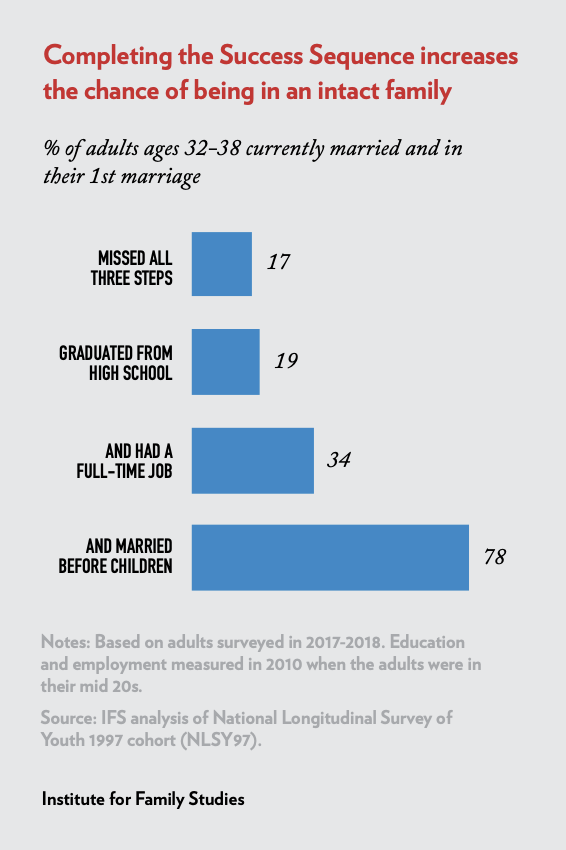

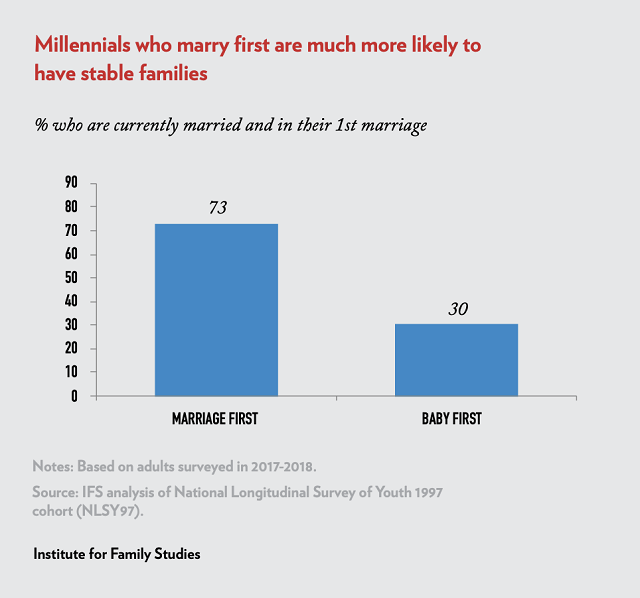

Why does the Success Sequence contribute to better mental health? Further analysis suggests that the sequence is closely linked to family stability, which is key to mental well-being. Millennials who married before having children are more likely to have stable marriages. Among Millennials who followed this path, 73% are in intact families (married and never divorced) by their mid-30s, compared with only 30% of those who had children before or outside of marriage.

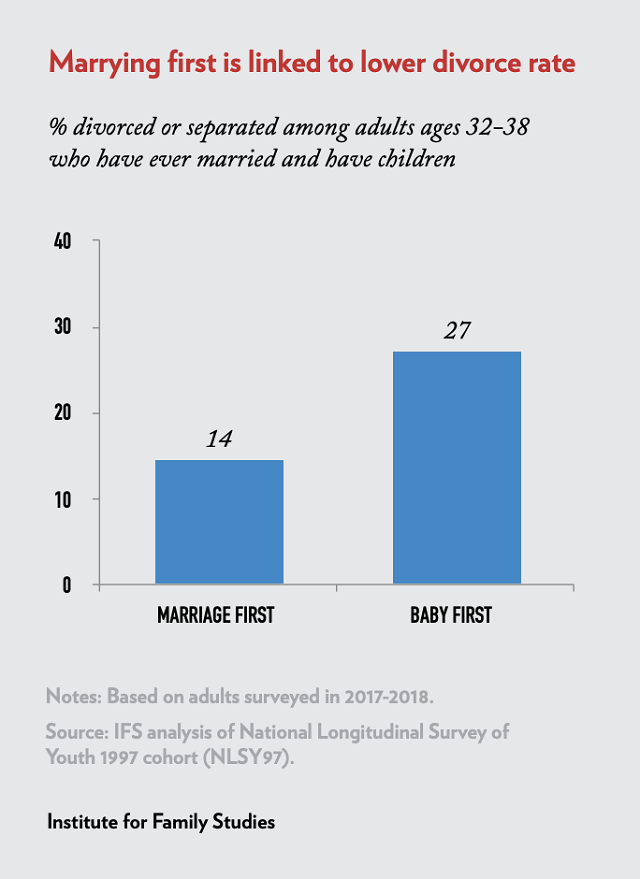

Furthermore, among Millennials who have been married and have children, those who became parents before marriage are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by their mid-30s compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%). Even after controlling for confounding factors like education, race, and family background, we find that marrying before having children is linked to a 32% decline in divorce among those who have ever married and have children.

Among the report’s other key findings:

Findings in this report are based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 cohort (NLSY97).

NLSY97 follows the lives of a national representative sample of American youth (with black and Hispanic youth oversamples) born between 1980 to 1984. This cohort is also considered the oldest group of Millennials. The survey started in 1997, when the respondents (about 9,000) were ages 12 to 17. The interviews were conducted annually from 1997 to 2011 and biennially since then.

Respondents who stayed in Round 18 (N=6,734) are spotlighted in this report. They were in their mid-30s (ages 32-38) when surveyed in 2017 to 2018. The findings are weighted to reflect the characteristics of the overall population of American Millennials who were born between 1980 and 1984. The minimal sample size for the subgroup analysis is 100 unless otherwise noted.

To measure mental health, a five-item short version of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) in NLSY97 was used. The items of the MHI-5 measure risks for suffering anxiety and depression, loss of behavioral or emotional control, and overall psychological well-being. Respondents were asked about how they felt during the previous month through a set of 5 questions, which include feeling nervous, feeling calm and peaceful, feeling downhearted and blue, being happy, and feeling so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer them up. Each question was rated on a 4-point scale: (1) All of the time, (2) Most of the time, (3) Some of the time, and (4) None of the time. The scores of the negative outcomes are reversely coded and scores of all five questions are combined into a mental health index range from 5 to 20. “Highly distressed” is coded as 1 standard deviation (S.D.) above the mean.

In the analysis of the Success Sequence, finishing high school and having a full-time job (working 35+ hours per week and 50+weeks a year) were measured when respondents were in their mid-20s. For more details about the methodology of the Success Sequence, please see the report The Millennial Success Sequence.

In this report, the term “Millennials” refers to adults born between 1980 and 1984, representing the oldest group of Millennials. The terms “Millennials” and “young adults” are used interchangeably, as are “mentally distressed” and “emotionally distressed.”

chapter 1: Navigating the Journey to Adulthood: Marriage, Parenthood, and Mental Health

The paths into adulthood for Millennials are more diverse than those of earlier generations. By their mid-30s, 45% of Millennials have married without first having a child, compared with about 70% of Baby Boomers when they were about the same age. Additionally, 35% of Millennials in this study have had children before or outside of marriage (compared to about 20% of Baby Boomers at the same age), and the remaining 20% of Millennials have never been married and are childless at ages 32 to 38.

Among young adults who are parents, there is almost an even split regarding the paths to parenthood. About 51% of Millennial parents in their mid-30s had children before or outside of marriage, while 49% took the path of getting married first before having children.

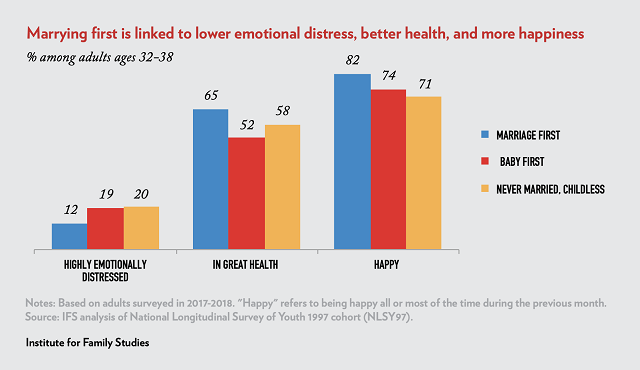

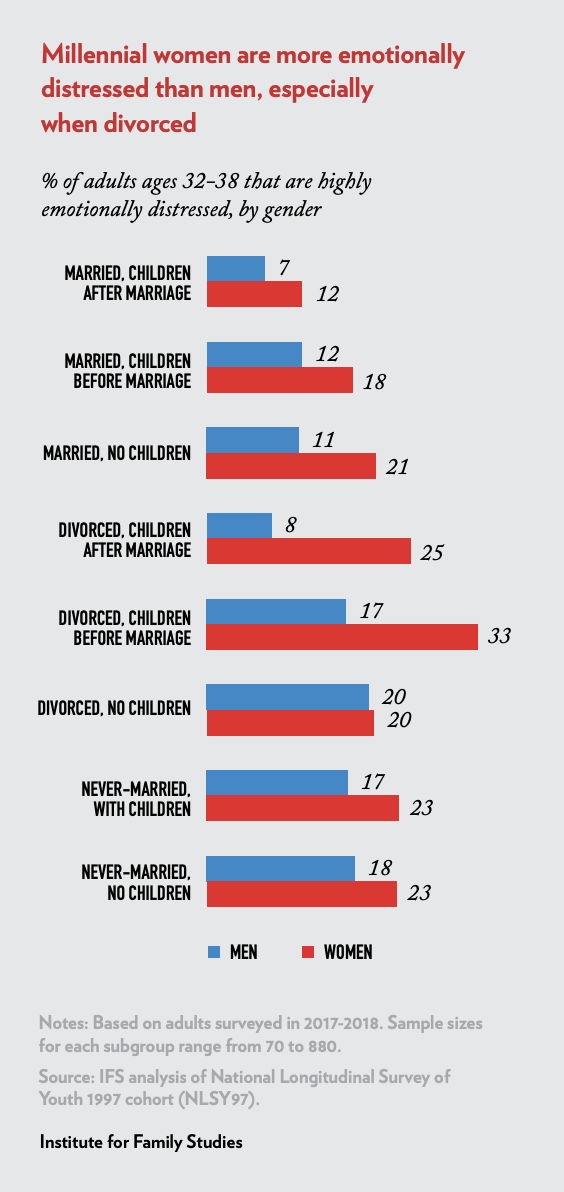

The order of marriage and parenthood matters for young adults’ health. Compared with their peers who had a child before marriage, Millennials who followed the path of “marriage first” are less likely to experience emotional stress and more likely to report being in great health and happy by the time they are in their mid 30s.1 For example, only 12% of Millennials who married before having a child report a high level of emotional stress, which is measured by a combination of mental health measures including depression, anxiety, and overall psychological well-being. In comparison, 19% of Millennials who had babies before marriage report a higher level of mental distress. Moreover, the group of Millennials who have never married and are childless report similar levels of mental distress as those who had babies before or outside of marriage.

Marrying first is not only linked to a lower chance of emotional distress, but also to better general health and overall happiness. Millennials who married before having children are more likely than those who had children first to report being in great overall health when reaching their mid-30s (65% vs. 52%) and being happy all or most of the time (82% vs. 74%).

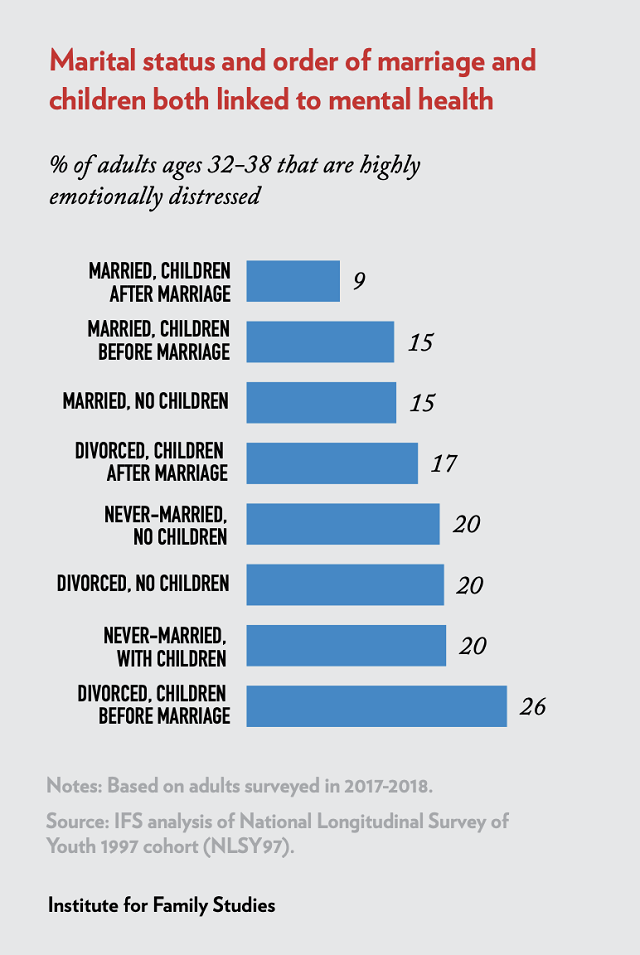

A closer look at different approaches to marriage and parenthood for Millennials in their 30s suggests that those who are currently married and had children after marriage have the lowest level of mental distress. Less than 10% of these adults reported high emotional stress, compared with 15% of Millennials who are married but either had children before marriage or are currently childless.

Divorce takes a toll on mental health. However, even among divorced young adults, the order of children and marriage is still linked to better mental well-being. Some 17% of divorced Millennials who became parents after marriage are highly stressed emotionally, compared with 26% of their peers who had children before marriage.

Millennials in their mid-30s who delay both marriage and parenthood (never married, childless) are equally likely to be emotionally stressed as their peers who have children but are not married. About 1 in 5 Millennials in these two groups experience high-level emotional distress, as do their peers who are divorced but do not have children.

These findings regarding mental health echo some of the results about Millennials’ family and financial status. We find that married Millennials who have children after marriage are most likely to be in the middle- and upper-income brackets (see more details in the Appendix). However, married and childless Millennials are better off financially than married Millennials who had children before marriage, yet the emotional stress levels in these two groups are similar. We also find that divorced and childless individuals are also better off financially than divorced Millennials who had children after marriage, but they have slightly higher rates of emotional distress. These findings suggest higher family income and better mental health do not always go handin-hand, especially when it involves children and marriage.

In addition to the order of marriage before having children, the Success Sequence includes two earlier steps: Getting at least a high school education and working full time. Our analysis finds that the Success Sequence is strongly linked to better mental health among young adults. For Millennials who complete all three steps of the sequence, the chance of being highly emotionally distressed is only 9% when they reach their mid-30s. In contrast, 30% of Millennials who missed all three steps are in mental distress at this life stage, and those who completed the education and work steps but didn’t marry before having a child are also more likely to be highly distressed (12%) when they are in their mid-30s.

It may seem logical to attribute better mental well-being to the financial success of young adults who followed the Success Sequence, but the findings suggest that even after controlling for income, the sequence remains a significant factor in the mental health of young adults. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress by their mid-30s are reduced by about 50% for young adults who have completed the three steps of the sequence, after controlling for a range of background factors including family income, education, gender, and race (see Table 1 in the Appendix for details).

To see exactly how the order of marriage and parenthood plays out for Millennials, we also looked at the impact of the Success Sequence among Millennials who have had children (about 70% of Millennials have had children by age 32 to 38). The findings are identical: Millennial parents who missed all three steps of the sequence are much more likely than others to experience mental distress. In contrast, the mental distress level is much lower, around 7%, among Millennial parents who have completed all three steps of the sequence (see figure in Appendix for more details).

Millennial women are consistently more likely than men to be emotionally distressed. Overall, about 19% of Millennial women in their mid-30s report high emotional stress, compared with 13% of Millennial men. Among Millennial women who missed all three Success Sequence steps, 38% are highly emotionally distressed at ages 32 to 38. The share is 22% for Millennial men who missed all three steps by their mid-30s. With the completion of each step of the Success Sequence, the emotional stress level generally goes down for both Millennial men and women, but the gender gap remains. Even among Millennials who have followed all three steps, women are still more likely than men to experience high emotional stress (12% vs.7%).

A similar gender gap also exists among Millennials who have children. Among Millennial parents who missed all three steps of the Success Sequence, 36% of mothers and 19% of fathers are highly emotionally distressed by their mid-30s. The gap is significantly reduced but remains among Millennial parents who have completed all three steps of the Success Sequence: only 5% of Millennial fathers and 10% of Millennial mothers who followed the sequence experience high mental distress by their mid-30s.

These findings are in line with longstanding patterns from psychiatry that women are more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression. Several potential reasons have been offered as to why women are more prone to emotional distress, including the fact that women experience more hormonal fluctuations that can trigger clinical depression or anxiety. For example, women are prone to particular forms of depression or anxiety that are specifically triggered by these hormonal changes, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression, or postmenopausal depression or anxiety, whereas men do not experience these conditions.

Looking at the different family paths Millennial men and women have taken, we find that overall, married women who have children after marriage enjoy better mental health than other women, with only 12% of them experiencing high emotional stress in their mid-30s. On the other hand, divorced Millennial women who had children before marriage have the highest levels of mental distress by their mid-30s. About 1 in 3 divorced Millennial women who had children outside of marriage are highly distressed.

In contrast, divorced Millennial women who had children after marriage suffer less emotional distress. About 1 in 4 of these women reported being highly emotionally distressed. This is similar to the emotional distress levels among never-married women (with or without children).

Young men’s emotional distress levels are lower overall than that of young women in most of these different family paths, except among young adults who are divorced but childless. An equal share of young men and women (20%) in this group experience a high level of emotional distress, which represents the highest level of emotional distress among Millennial men in their mid-30s. Millennial men who are currently married and have children after marriage experience the lowest levels of mental distress. Interestingly, divorce doesn’t take a heavy toll on young men who are divorced but have children after marriage. Only 8% of men in this situation experience high emotional distress, which is similar to the rate for men who are married and had children after marriage.

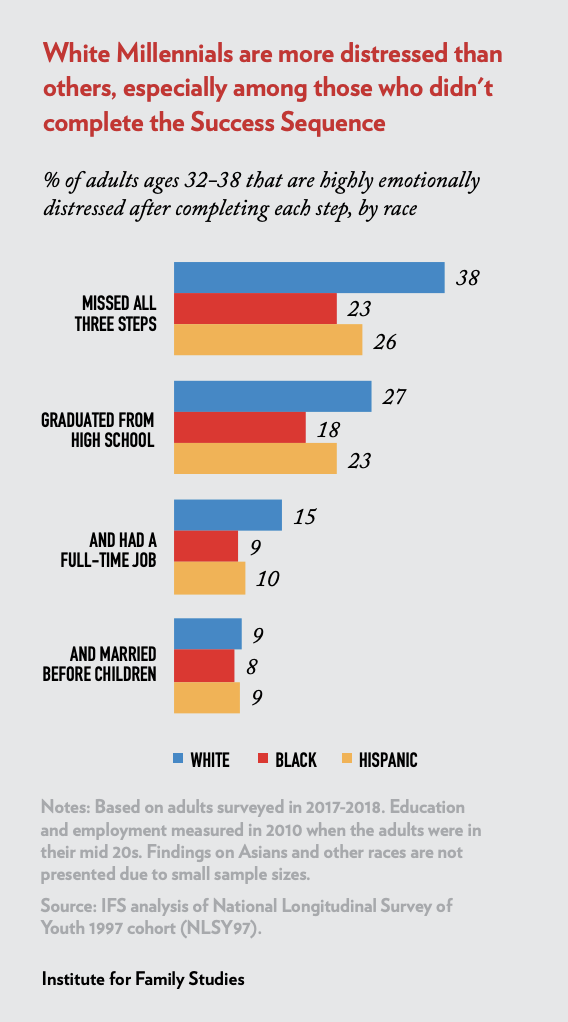

In contrast to the financial success story presented in the previous IFS report on the Success Sequence, where white Millennials were consistently less likely than black and Hispanic Millennials to be in poverty, white Millennials do not have an advantage over other young adults when it comes to emotional well-being. In fact, they are generally more likely than other races to experience emotional distress.2 Among young adults who have missed all three steps of the sequence by the time they are in their 30s, white young adults are much more likely to report that they are highly emotionally stressed (38%) compared with black young adults (23%) and Hispanics (26%), despite the fact that white young adults in this situation are much less likely to be in poverty than the other two groups.

With completion of each step of the Success Sequence, the racial gap narrows. For Millennials who followed all three steps, the share of highly emotionally stressed young adults drops to 9% for whites, 8% for bBlacks, and 9% for Hispanics. The racial gap in emotional well-being is almost closed.

Previous studies on Millennial health showed that Millennials in majority black and Hispanic communities have significantly lower rates of depression than those in majority white communities, with some hypothesizing that these differences could be due to under-diagnosis in communities of color. Our analysis of NLSY data support a lower rate of symptoms of depression and anxiety among black and Hispanic individuals. Notably, the self-report nature of this data suggests that lower rates of depression and anxiety symptoms among black and Hispanic individuals may not be due to underdiagnosis and that other factors may be at play.

Taken together, the Success Sequence’s link to both economic success and emotional well-being suggests that following the sequence offers a clear path to closing the racial gap, not only in terms of economic well-being but emotional well-being as well.

The Success Sequence benefits Millennials’ mental health not only through the financial success it brings but also because it is linked to another important factor in mental health: family stability.

Millennials who followed the sequence of marrying before having children are more likely to have stable marriages. Among Millennials who married before having children, 73% are in an intact family (married and have never been divorced) by the time they are in their mid-30s, compared with only 30% of Millennials who had children before or outside of marriage. Furthermore, among Millennials who have been married and have children, those who became parents before marriage are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by the time they reach their mid-30s, compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%).

Following all three steps of the Success Sequence—getting at least a high school education, working full-time, and marrying before having any children—leads to much higher family stability by the time Millennials reach their mid-30s. Close to 80% of young adults who followed this path are married and have never divorced, compared with 34% of young adults who missed the step of marrying before children, and 17% of young adults who missed all three steps.

Moreover, after controlling for a range of sociodemographic factors, young adults who followed the three steps of the Success Sequence are four times more likely to be living in an intact family in their 30s compared with their peers who didn’t follow the sequence. The fact that family stability is key to mental health is supported by multiple lines of research. For children, parental divorce is a large and consistent risk factor for anxiety, depression, and substance use. Family stability (as in marital stability without divorce) has repeatedly been shown to lead to better financial and educational outcomes for children, which in turn reduces the risk of mental health problems.3 Another key way that family stability may mediate improved mental health outcomes for children is by protecting them from physical and sexual abuse, which greatly increase the risk of psychiatric problems.4 Overall, children from families with married biological parents are three to 10 times less likely to experience physical abuse compared to children in step-families or in households headed by single parents with or without romantic partners; they are also five to 20 times less likely to experience sexual abuse.5

Family stability is also important for the mental health of adults. Reports based on large and nationally representative surveys have shown that both men and women who marry and remain married have lower rates of depression, anxiety, suicide, and suicide attempts compared to those who are single, widowed, or divorced.6 These findings parallel the conclusions of this research brief.

There are many contributing factors to mental health, but family stability is clearly a major factor. The findings of this report are in line with decades of research from psychology showing that relationships are fundamental to human happiness and well-being. Furthermore, among the many relationships that affect us, marital relationships tend to have the greatest bearing on our emotional (as well as physical) health.

The mere act of being married raises the probability that someone is very happy by a substantial amount. In a prior analysis of data (1972-2021) from the General Social Survey, 37% of those who were married reported they were very happy compared to 18% who were single, widowed, or divorced.

There are many potential ways that marrying before having children favors greater relationship stability compared to when the sequence is reversed. Divorce is one measurable indicator.

Divorce is a major stressor in life, and it is linked with an increased risk of anxiety, depression, and alcohol abuse, along with other negative mental health outcomes. When we limit the analysis to Millennials who have been married and have children, a clear pattern emerges regarding the order of marriage and having children and family stability. Millennials who became parents before getting married are about twice as likely to be divorced or separated by the time they are in their mid-30s, compared with their peers who married before having children (27% vs. 14%).7 Even after controlling for confounding factors like education, race, and family background, we find that marrying before having children is linked to a 32% decline in divorce among those who have ever married and have children.8

Both groups are married with children. But what explains why the group who had children before marriage is more likely to experience divorce than those who had children after they were married? Many factors could be at play. Couples who have children before marriage may not have fully established the foundation of their relationship, such as commitment and communication, which often leads to increased marital strain. Additionally, the stressors associated with unplanned pregnancies and early parenthood may exacerbate existing relationship challenges.

Moreover, our findings suggest that Millennials who become parents before marriage tend to have children at an earlier age than those who marry first (with a median age for first birth of 21 vs. 28), but they marry later than the “marriage first” group (at 26 vs. 24). With an extended gap between first birth and marriage, it is possible that some Millennials who follow this path may not necessarily marry the parent of their children, further complicating family relationships. These complexities in family dynamics could contribute to the increased likelihood of divorce among couples who had children before marriage.

The Success Sequence—completing at least a high school education, securing full-time employment in their 20s, and marrying before having children—not only offers a promising path for young adults to achieve economic success but is also closely linked to emotional and mental well-being. Moreover, the ways in which the Success Sequence contributes to mental health are not limited to financial success but also to the higher levels of family stability associated with following this path.

Our findings demonstrate that young adults who’ve followed the three steps of the Success Sequence experience significantly better mental health by their mid-30s compared with those who have not. This is true even after accounting for various background factors such as income, gender, and race. The odds of experiencing high emotional distress are reduced by about 50% for those who have completed each step.

Family stability emerges as a crucial factor in the mental well-being of Millennials. Those who marry before having children are more likely to maintain intact families, with 73% remaining married by their mid-30s. In contrast, those who have children before marriage face much higher rates of divorce and separation. The extended gap between first birth and marriage in this group often complicates family relationships, potentially leading to greater family instability and subsequent mental health challenges.

Given the mental health crisis among Millennials and young adults, it is important for young people to understand what patterns are more likely to help them form families that lead to better mental health. Unfortunately, a variety of factors in contemporary culture have made it more difficult for young people to form stable marriages and families.

One factor is that marriage is less likely to be valued than work or education. A 2023 Pew Research Center report noted that 88% of parents agreed it was “very” or “extremely” important for their children to have an enjoyable job, and 41% said it was very or extremely important for their children to graduate from college, whereas only 20% of parents attached the same level of importance to their children getting married. These goals run in contrast to decades of sociological data that conclude a good marriage is more important to well-being than other factors, including career.9

This mismatch between those goals we tend to prioritize and what actually leads to enduring well-being occurs on an individual level as well. Predicting how we are going to feel in a given circumstance is known as affective forecasting. Humans make such predictions every day without thinking, and these predictions shape life priorities. Surprisingly, humans are relatively poor judges of what leads to enduring well-being.

Psychological science has repeatedly shown that relationships are the most important factor for well-being and happiness.10 The most important relationship is with one’s romantic partner or spouse. Helping young people understand the importance of relationships to well-being is critical to helping them prioritize marriage.

Today’s young adults receive ample training and guidance in education and career, but when it comes to getting married and having children, most people “just wing it.” Among the key components of the Success Sequence—education, work, marriage, and children—training and guidance on healthy marriages and family life are severely lacking.

As we suggested in previous reports, we should teach the Success Sequence in schools and promote it via public campaigns. For those who care about both the economic and emotional well-being of today’s young adults—policymakers, educators, business and community leaders, influencers, as well as parents—it is time to help young adults understand how following each step in the Success Sequence will increase their chances of a financially and emotionally healthy life.

The “Marriage first” group includes those who had children after marriage, regardless of their current marital status, as well as those who are currently married but do not have children. The “Baby first” group includes those who had children before marriage or outside of marriage, regardless of their current marital status.

Overall, 17% of white Millennials in their mid-30s reported high emotional stress, compared with 14% of Black Millennials, 14% of Hispanic Millennials, and 11% of Asian Millennials, according to NLSY97 data.

David Blankenhorn. Fatherless America: Confronting Our Most Urgent Social Problem. (New York City: Harper Perennial, 1996); David Popenoe. Life Without Father: Compelling New Evidence That Fatherhood and Marriage Are Indispensable for the Good of Children and Society. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999). Also: Melissa Kearney. The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023).

Jutta Lindert, et al., “Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: A systematic review and metaanalysis.” International Journal of Public Health 59, no. 2 (2014): 359-372.

Felicitas Auersperg, et al., “Long-term effects of parental divorce on mental health: A meta-analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 119 (2019): 107-115. Brad Wilcox. Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization. (New York City: HarperCollins, 2024).

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. The Effects of Marriage on Health: A Synthesis of Recent Research Evidence. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 2007). Sohrab Iranpour, et al., “The trend and pattern of depression prevalence in the U.S.: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005 to 2016.” Journal of Affective Disorders 298, part A (February 2022): 508-515. W. KyungSook et al., “Marital status integration and suicide: A meta-analysis and meta-regression.” Social Science & Medicine, 197 (2018): 116-126. T.J. Bommersbach, “National trends of mental health care among US adults who attempted suicide in the past 12 months.” JAMA Psychiatry 79, no. 3 (2022): 219-231.

Marital status was measured at ages 32 to 38, accounting for multiple divorces and remarriages.

The regression model includes work status and whether the respondents lived with both of their parents during their teenage years.

Op. Cit, Wilcox. Get Married.

Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz. The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023). M.E.P. Seligman. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. (New York: Atria Books, 2011).

About the Authors

Wendy R. Wang, Ph.D. is Director of Research at the Institute for Family Studies. She has published widely on topics including marriage, gender, work, family, happiness, and well-being. Dr. Wang is a former Senior Researcher at Pew Research Center and the lead author of the Pew Research Center report, Breadwinner Moms, among other Pew reports.

Samuel T. Wilkinson, MD, is Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine and the Associate Director of the Yale Depression Research Program. His research specializes in innovative treatments for depression, including novel pharmacological and neuromodulation techniques. Dr. Wilkinson is also the author of the book Purpose: What Evolution and Human Nature Imply about the Meaning of Our Existence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank IFS senior fellow Brad Wilcox for his insights and substantive feedback on this report. We would also like to thank Alysse ElHage for editing the report and Brandon Wooten for its design.

May 2025 | by John Iceland, Jaehoon Cho

May 2025

by John Iceland, Jaehoon Cho

This research brief focuses on differences across household types in income, non-income resources, such as wealth, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, such as age and education.

Download PDFAbstract

Married-couple households are more affluent, less likely to be poor, and experience fewer hardships than other types of households, such as single-parent families or people living on their own. This research brief explores why, focusing on differences across household types in income, non-income resources, such as wealth, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, such as age and education.

In our recent study, published in Demographic Research, we find that married-couple households experience fewer hardships than other households while single-parent families with children experience the most. Other household types, such as cohabiting couples and people living alone, fall in between. The biggest reason for the married-couple advantage is wealth—married couples often have more savings and assets to fall back on. Income also plays a significant role, followed by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

In short, the income- and wealth-building capacity of married-couple households are important for helping them avoid hardships. Meanwhile, a more moderate portion of the married-couple household advantage reflects the selection of more fortunate demographic and socioeconomic groups into marriage—for instance, people with higher levels of education are more likely to marry than others.

May 2025 | by Erik Randolph

May 2025

by Erik Randolph

A two-part IFS policy brief on how to eliminate marriage penalties from the tax code and safety-net programs.

Download PDFThe U.S. individual income tax structure and the safety-net assistance system exact financial penalties on married couples, which worsen when children are in the family. The effect of these penalties is the opposite of what public policy should be. Research has established that society benefits immensely from stable and healthy marriages. This policy brief is divided into two sections. Section 1 focuses on the U.S. Tax Code and restoring the income tax to its primary purpose, while eliminating the marriage penalty. Section 2 presents a way for Congress to eliminate marriage penalties from safety-net programs.

An IFS research brief on the fertility-boosting benefits of expanding the Child Tax Credit (CTC).

Download PDFWhat would happen to American fertility if the child tax credit were appreciably increased? Many are skeptical of the influence of cash transfers on fertility, but that skepticism is misplaced. Cash-for-kids works. It is relatively cost-effective, and its fertility effects help families achieve their own stated family goals. The pronatal outcomes of an increased child tax credit are a good reason to support such an investment.

Key Findings:

April 2025 | by Grant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox

April 2025

by Grant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox

This IFS report examines family formation among working-class men, defined as men without college degrees, within the context of distinct employment environments. We also examine differences in married family formation rates between working-class and college-educated men, and the extent to which these differences might be explained by differences in pay, benefits, and stability.

Download PDFGrant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox, Good Jobs, Strong Families. How the character of men's work is linked to their family status (The Institute for Family Studies, Penn’s Program for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society (PRRUCS), 2025)

Media Coverage

John DiIulio, "The best natalist policy: good jobsThe makings of a second Baby Boom," UnHerd, May 26, 2025

Chris Bullivant, Grant Martsolf, Brad Wilcox, "Is the collapse of blue-collar marriage a foregone conclusion," The Washington Examiner, April 30, 2025

Grant Martsolf, "Good jobs, strong families in working-class America," Family Studies, April 29, 2025

Introduction

Over the last half century, the U.S. economy has shifted, moving away from manufacturing and towards being an information and service economy. The mid-1980s, for instance, were punctuated by news of the closures of major steel manufacturers, including Homestead Works, Aliquippa Works, and Duquesne Works in Pittsburgh, PA, and Republic Works in Youngstown, OH. The closures were part and parcel of a period of massive deindustrialization. Between 1984 and 2004, the U.S. economy lost between 6 and 7 million manufacturing jobs that provided reliable and high-paying employment with good benefits for millions of working-class Americans.

The move away from manufacturing had a significant impact on America’s working class. Real wages of the median Americans with a high school diploma or less (a common measure of “working class”) declined by 11% between 1979 and 2019, while those of the median worker who had finished college increased by 15 percent. Many industrial communities, especially across America’s “Rust Belt,” experienced significant disinvestment and fell into blight. These economic shifts, both in the Rust Belt and nationwide, took a devastating toll. They pushed working-class men’s labor force participation down and led to declines in religious and secular expressions of community life in areas hit hardest by deindustrialization. Families not only broke apart but failed to form. In the wake of this economic dislocation and social breakdown, deaths of despair—that is, deaths from drug overdoses, suicides, and alcoholism—surged among working-class women and especially men.

The transformation of the American economy has been especially impactful on working-class men. As manufacturing receded, employment in service industries surged, especially in healthcare, financial, and information services. Many of these service jobs require a college degree. And most of the significant growth in jobs that do not require a college degree has been concentrated in industries and occupations that are female dominated. Since 1990, the healthcare industry alone has added roughly 9 million jobs to the US economy. Nearly 80% of Americans who do not have a college degree and work in healthcare are women.nbsp;In fact, declines in real wages for working-class workers were concentrated among men; working-class women have seen their real wages rise since 1979.

Over this same period, Americans have also experienced a significant reduction in marriage and family stability. Since 1970, the marriage rate has fallen by more than 60% to the point where only about 1 in 2 adults are married. Declines in marriage and family stability have been especially precipitous for working-class Americans since 1980. For instance, only 39% of non-college-educated Americans ages 18-55 are married, compared to 58% of college-educated Americans.

Our hypothesis in this Institute for Family Studies (IFS) report is that the nature and character of work play a key role in affecting male marriageability. We contend that features of work like job stability, predictable hours, good benefits, and high pay help men to flourish and, in turn, elevate their appeal as husbands. Moreover, we note that class divides in marriage today are driven in part by differences in the character of work, with college-educated men generally benefiting, in terms of marriage and family formation, from jobs that are more stable, predictable, higher status, and remunerative. But we also suspect that the character of work varies among working-class men themselves, such that some jobs among working-class men are more likely to facilitate marriage and family formation than others.

In this report, we examine family formation among working-class men, defined here as men without college degrees, within the context of distinct employment environments. We also examine differences in married family formation rates—measured here in terms of being married with children at home—between working-class and college-educated men, and we investigate the extent to which these differences might be explained by differences in “good job” variables—primarily differences in pay, benefits, and stability. We then explore differences in the rates of married family formation among working-class men by industry and estimate the extent to which differences across industries are explained by the same “good job” variables. We conclude with a discussion of how public policies might better support working-class men in their jobs to improve their family prospects.

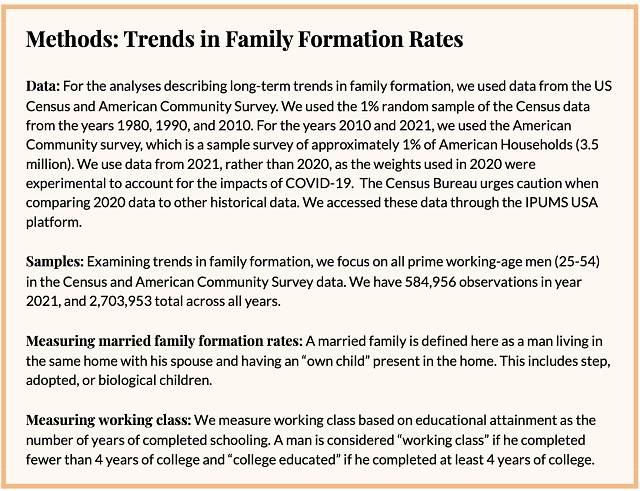

Part 1: Family Formation Among Working-class Men

Trends in family formation rates

In this section, using historical Census data from 1980-2021, we discuss recent family formation trends among working-class men. Working class throughout this report is operationalized as completion of less than a college education. Here, college education is defined as completion of at least four years of college. Importantly, this is slightly different than the operationalization of “working class” because the measures of educational attainment in historical Census data are slightly different from the CPS data used in subsequent analyses.

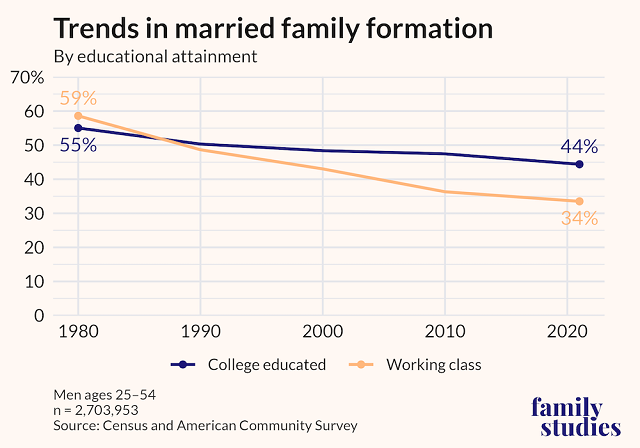

There is ample evidence that college-educated Americans are more likely to get married, stay married, and avoid having children out of wedlock. This is partly because more educated men and women have more stable incomes, more shared assets, greater civic supports for their marriages, and networks that are dominated by married peers, as Wilcox argued in Get Married.

However, this has not always been the case. In fact, before the 1980s, men who did not complete college had higher rates of married family formation compared to those who did complete college. In our analysis of Census data, we found that in 1980, 59% of all prime working-age men (ages 25-55) who did not complete college were married with children living in their homes, compared to 55% of men who did complete college.

Over the course of the next 40 years, all men in America were increasingly less likely to be married and living with children. By 2021, only 37% of prime working-age men were married living with children compared to 58% in 1980 (Figure 1). But the overall decline in married family formation was more significant for men who had not completed college. Over the last 40 years, men who had not graduated from college were now actually less likely than college-educated men to be married and living with their own children. By 2021, 34% of non-college-educated, prime working-age men were married and living with their own children compared to 44% of college-educated men.

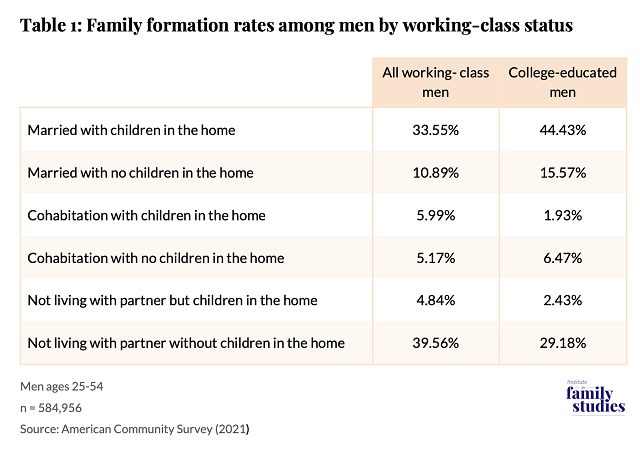

We examine more closely family formation rates among working-class men ages 25-55 in 2021 (Table 1). We found that working-class men (33.50%) were much less likely to be married with children living in their homes compared to college-educated men (44.39%). At the same time, they were much more likely to cohabit with children in the home (3.44% vs. 0.93%) and to be living with no partner and without children (41.36% vs. 31.83%).

Part 2: Examining Married Family Formation by Class and the Impact of Good Job Variables

Married family formation rates by class

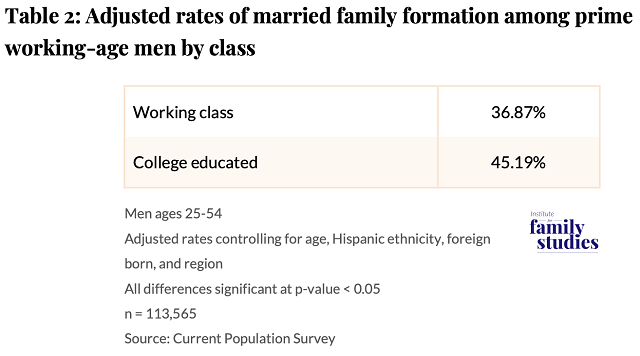

This section compares all college-educated versus working-class men. We are interested primarily in the links between class, workplace environment, and family status. For this analysis, we use data from the Current Population Survey from years 2021-2024. We used regression models to estimate predicted probabilities of having a married family by education, which we view as a proxy for class. In our sample of 113,656 prime working-age men, we find that working-class men were 8 percentage points less likely than college-educated men to be married and living in the home with their children (Table 2). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A3.

Mediation of differences across class by good job variables

We then examine the extent to which differences in married family formation across classes might be explained by differences in the types of jobs that working-class and college-educated men hold (i.e., good job variables). To determine the extent to which differences could be explained by good job variables, we performed a mediation analysis using the Barron and Kenney framework. To do this, we must first establish that good job variables are associated both with class and married family formation. If so, we can test the mediation impact of good job variables on marriage formation rates.

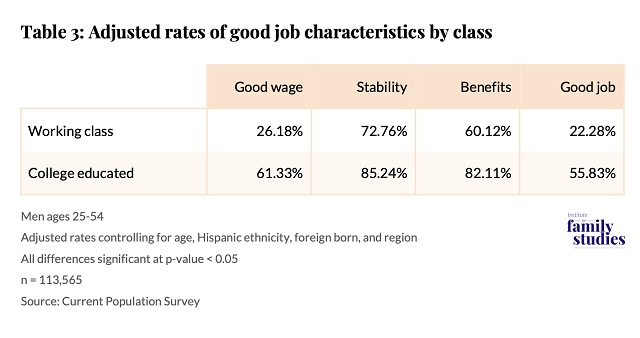

We first compare good job variables across working-class and college-educated men. We find significant differences across classes. Most notably, a majority of college-educated men (61.33%) make a “good wage” (i.e. >$60,000 per year) compared to a minority of working-class men (26.18%). College-educated men are also much more likely to have stable jobs. They are also about 20 percentage points more likely than working-class men to have employer-sponsored health benefits. They are much more likely to have all three good job characteristics at their current employer (Table 3). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A4.

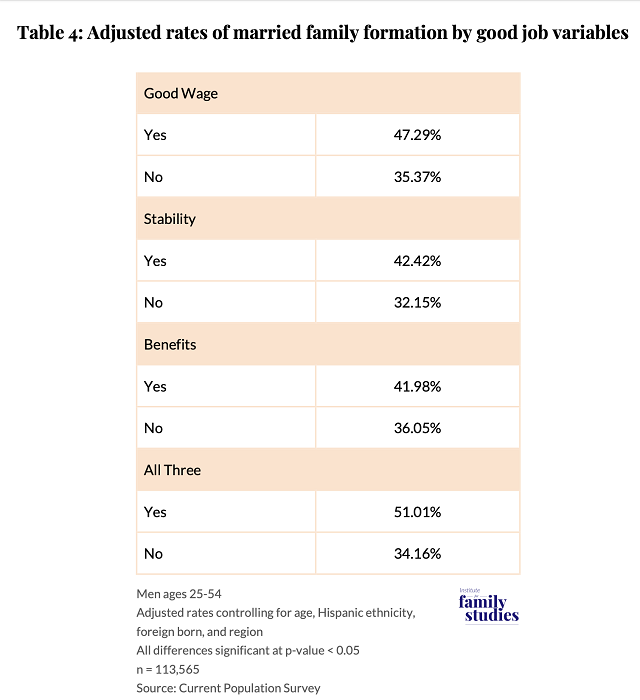

These good job characteristics are also correlated with married family formation rates. We find that those with good job characteristics are much more likely to be married family men. Those with all three of these good job characteristics are 17 percentage points more likely than those who do not have all three of these characteristics to have a married family (Table 4). Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A5.

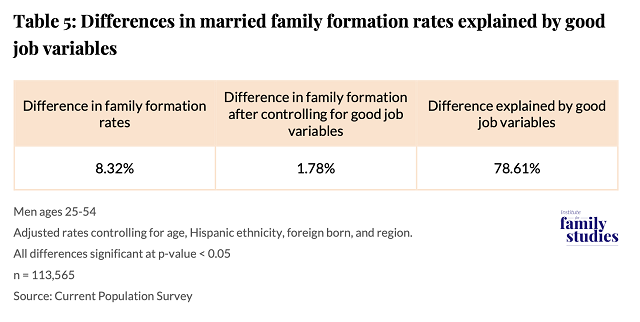

Finally, we examined the extent to which the good job variables mediate the relationship between class and family formation rates. Table 5 shows that good job variables are in fact a significant meditator between class and married family formation. These good jobs variables explained nearly 80% of the adjusted differences in married family formation rates by class (Table 5). This is a striking finding. It underlines the ways in which the character of college-educated men’s jobs probably helps explain why they are markedly more likely to get and stay married than working-class men. Of course, we cannot determine the direction of causality here. All that we can say is the class divide in marriage between college-educated and working-class men is closely tied to the class divide in the character of men’s work. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A3.

Part 3: Examining Married Family Formation by Industry Among Working-class Men

Married family formation rates by industry

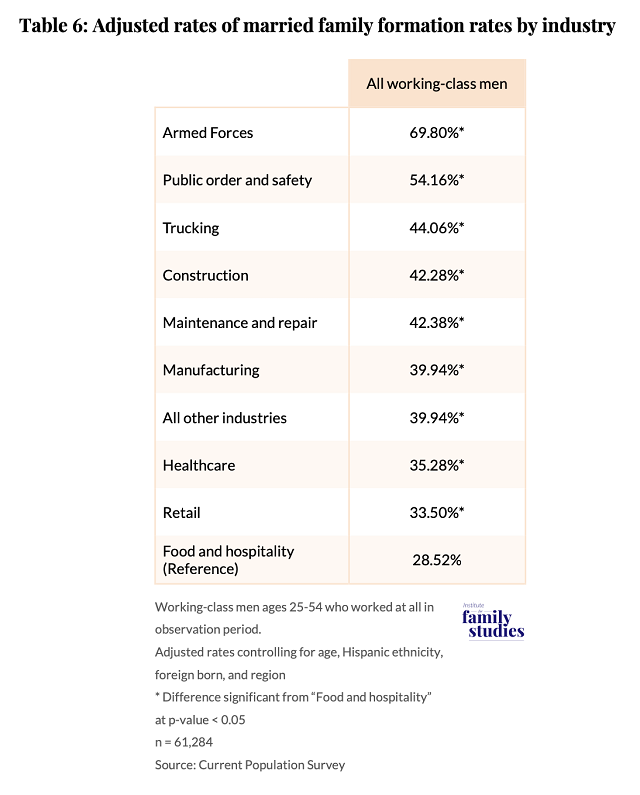

Patterns of married family formation for working-class men differ by employment industry. In this section, we focus exclusively on men who report having worked during the observation year. Only those who worked at some point during the observation year will have data on primary industry. For this analysis, we use data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) from years 2021-2024. Table 6 indicates wide variation across industries in terms of the rates of married family formation for working-class men. The highest married family formation rates among working-class men are in the armed forces and public order and safety, followed by trucking, construction, and maintenance and repair. The high rates of married family formation in the armed forces are consistent with earlier research indicating that the armed forces continue to support marriage and family life. Surprisingly, manufacturing falls in the middle. By contrast, the lowest shares of married family formation for working-class men are in healthcare, retail, and food and hospitality. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A6.

Mediation of differences across industries by good job variables

For working-class men, there is clearly variation between industry and family structure. How much are differences in married family formation rates across industries linked to differences in “good job” variables, including pay, health insurance benefits, and stable employment? In this section, we take up this question.

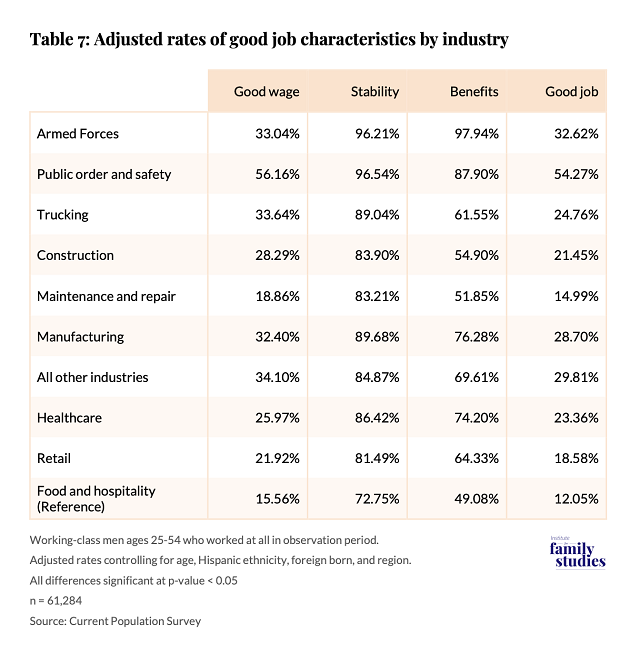

To determine the extent to which differences could be explained by these good job variables, we again perform a mediation analysis using the Barron and Kenney framework. In examining the relationship between industry and good job variables, we find that some industries have more good job characteristics than others, as Table 7 indicates. Public order and safety, armed forces, trucking, and manufacturing have higher rates of good wages, while retail, food and hospitality, and maintenance and repair have significantly lower rates. Likewise, there were significant differences in job stability across industries with public order and safety, manufacturing, armed forces, and trucking enjoying the highest rates of stability, while food and hospitality had the lowest. In terms of benefits, public order and safety, manufacturing, trucking, healthcare, and, especially, armed forces had the highest rates of uptake of employer sponsored health insurance, while construction, food and hospitality, and maintenance and repair had the lowest. Again, our results here are indicative of the marriage- and family-friendly character of military jobs. Overall, public order and safety, manufacturing, construction, and trucking had the highest rates of all three good job characteristics, while retail, maintenance and repair, and especially food and hospitality had the lowest rates. We show the detailed regression results used to generate these adjusted rates in Appendix Table A7.

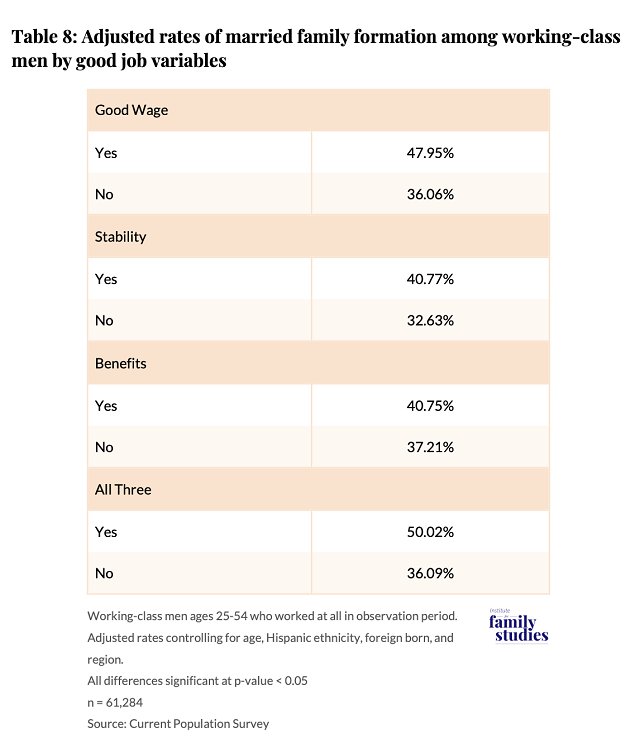

We also examined the relationship between family formation rates and good job variables within the Part 3 sample. Table 8 indicates that each of the good job variables is consistently correlated with higher rates of married family formation for working-class men. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A8.

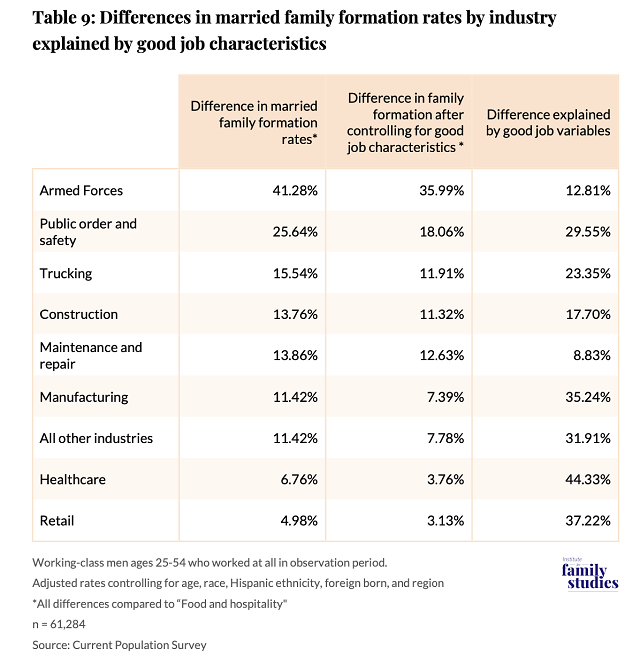

Finally, we examined the extent to which the good job variables mediated the relationship between industry and married family formation rates. Table 9 shows that good job characteristics are in fact a mediator between industry and married family formation for most sectors of the economy, but the amount of difference in married family formation rates explained by good job characteristics varies significantly across industries. The good job characteristics explain between 8-44% of the difference in married family formation between each of the industries compared to the food and hospitality industry. Regression coefficients used to produce these adjusted rates are shown in Appendix Table A6.

Conclusion

This Institute for Family Studies report suggests that both the nature and character of men’s work play a major role in determining whether men marry and form families. One big reason that working-class men are less likely to form married families seems to be that they have lower quality jobs—jobs marked by less income, less stability, and lower benefits. These findings must, however, be interpreted with caution. We do not show a direct causal relationship between good jobs and married family formation here, though we do show that having a good job is linked to men’s marital and family fortunes. To wit: prime-aged men with good jobs are markedly more likely to be married with children than men in lower quality jobs. So, consistent with the broader literature on work, men, and marriage, we think that access to good jobs increases the odds that men marry and form families.

Moreover, we document that differences in job quality help explain, statistically, almost 80% of the differences in the married family formation rates between working-class and college-educated men. This is a striking finding. Class differences in men’s work are clearly tied to class differences in marriage and family formation. The clear implication here is that men are more likely to be married with children when they are well paid, their jobs are stable, and their benefits are good.

Moreover, among working-class men, the findings of this IFS report suggest that having a good, working-class job appears to help explain differences among working-class men in married family formation rates across industries. More concretely, the fact that sectors like public order and safety, trucking, and manufacturing often have higher pay, greater job stability, or better benefits may help explain why men in these jobs also have comparatively high levels of married family formation. Undoubtedly, the good job characteristics that are more likely to define these sectors help explain why men who serve in these jobs are the working-class men most likely to be married with children.

In our analysis of industries and married family formation among working-class men, our good job variables do not explain all the difference in married family formation rates across industries among working-class men. There are likely other differences in job characteristics across the industries that we could not measure that may influence married family formation. We were particularly struck by the exceptionally high rates of family formation for men serving in the armed forces, which are not completely explained by our specific measures of good job characteristics. It may be that the military has a culture that is more friendly to marriage and family formation, or that the extra housing benefits (which we did not measure) extended to married service members make marriage more attractive to men in the military.

We also observed that healthcare, retail, and food and hospitality had lower levels of married family formation. This could be because many of these jobs are marked by erratic and unpredictable schedules that make it difficult to forge a strong and stable family. Many cities and states have attempted to alleviate this problem by legislating predictable schedules with some success.Some sectors—like food and hospitality—may also be associated with a culture of late nights and substance use that is not conducive to forming strong and stable families. Patterns like these undoubtedly help explain the clear differences we document between different sectors of the economy and trends in working-class men’s family formation.

Likewise, we also recognize an important selection effect is likely at play in our analysis. It is possible that these findings can also be explained by the fact that men who are best able to obtain good jobs also tend to have personal traits and social skills that are consistent with the ability to find a mate and form a family. Certain sectors—the armed forces, for instance—may attract and retain men who are especially reliable and responsible, and these underlying traits may also make them more attractive husbands and fathers. Moreover, working-class men are also likely to seek out better employment once they are married and have children.Marriage and family motivate men to seek out certain kinds of work, as well.

In conclusion, this Institute for Family Studies report shows that men who are employed in stable, good-paying jobs with decent benefits are markedly more likely to be married with children. Given this social fact, we think that employers and policy makers should aim to increase the share of high-quality jobs to American young and middle-aged adults, even as educators and policy makers seek to increase the share of young adults who are prepared to fill these jobs. When it comes to fostering work that is both more humane and remunerative, this requires taking a page from both the progressive playbook—e.g., Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance, which requires large businesses in the service sector to make workers’ schedules more predictable—and the conservative playbook—e.g., reducing regulatory burdens to expanded gas and oil exploration, thereby opening up more high-paying jobs in the energy sector. The exceptionally high rates of marriage and family formation among working-class men serving in the military also suggest that public policies designed specifically to help married families are also worth considering. Doing all these things might very well boost the fortunes of not only American men but also American families.

April 2025 | by Nicholas Zill

April 2025

by Nicholas Zill

An IFS research brief authored by Nicholas Zill that explores how family structure impacts student grades and classroom conduct.

Download PDFIntroduction

The last quarter century has seen a dramatic increase in grade inflation on student report cards in elementary, middle, and high schools throughout the United States. So much so that a student’s grade point average (GPA), which was once as useful as SAT or ACT scores, has become almost worthless as a predictor of how well the student would do in college or graduate school. And high school graduation rates have continued climbing even as the 12th-Grade results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) have remained stagnant or even declined. There has also been a notable decline in disciplinary actions by schools for student misconduct or lack of application.

Progressive education reformers have sought to make family background less of a determinant of how well a student does in school. Yet evidence from two nationwide household surveys of parents conducted nearly a quarter of a century apart demonstrate that family factors, such as marital stability, parent education, family income, and race and ethnicity, are as important as ever—or even more so

April 2025 | by Lyman Stone

April 2025

by Lyman Stone

Fact sheet 3 from the IFS Homes for Young Families report addresses what Americans desire most when it comes to housing.

Download PDFHousing is a core part of the family formation process, yet surprisingly little is known about what kinds of houses Americans want for their families. We remedy that gap in our recent report, Homes for Young Families: A Pro-family Housing Agenda, which presents evidence from a survey of nearly 9,000 Americans ages 18-54.

April 2025 | by Lyman Stone

April 2025

by Lyman Stone

Fact Sheet 4 from the IFS Homes for Young Families report explores the overwhelming desire of most Americans for single-family homes.

Download PDFToday, apartments as a share of home construction are at their highest level in decades. This is concerning since, as we show in Homes for Young Families: A Pro-family Housing Agenda, almost nobody in America wants to raise a family in an apartment. Our survey of almost 9,000 Americans finds a broad-spectrum rejection of apartment living across every single demographic group surveyed.

April 2025 | by Lyman Stone

April 2025

by Lyman Stone

Fact Sheet 5 from the IFS report, Homes for Young Families, shows that safety is the most important factor shaping the housing decisions of young Americans.

Download PDFFor decades, one of the dominant trends in American housing geography has been suburbanization, which has always been associated with public narratives around crime. In Homes for Young Families: A Pro-family Housing Agenda, our survey of almost 9,000 Americans finds that safety is the single most important factor shaping the housing decisions of young families. No amount of affordability or amenities will ever be enough to convince a family that a neighborhood where they feel unsafe is a great place to raise kids.

Interested in learning more about the work of the Institute for Family Studies? Please feel free to contact us by using your preferred method detailed below.

P.O. Box 1502

Charlottesville, VA 22902

(434) 260-1048

For media inquiries, contact Chris Bullivant (chris@ifstudies.org).

We encourage members of the media interested in learning more about the people and projects behind the work of the Institute for Family Studies to get started by perusing our "Media Kit" materials.

$75,000 by December 31

Your Support!